Ipswich Journal 1872 by an anonymous reporter.

This descriptive piece opened with a lengthy paragraph devoted to mist creeping around the streets of Ipswich, but eventually described an early morning trip by steamer from Ipswich to Harwich:

“The clock strikes eight, the streets look cheerless, the shops are not yet opened, and few people are abroad, the postman and the milkman go from house to house and their knocks are heard like fog signals in the mist.

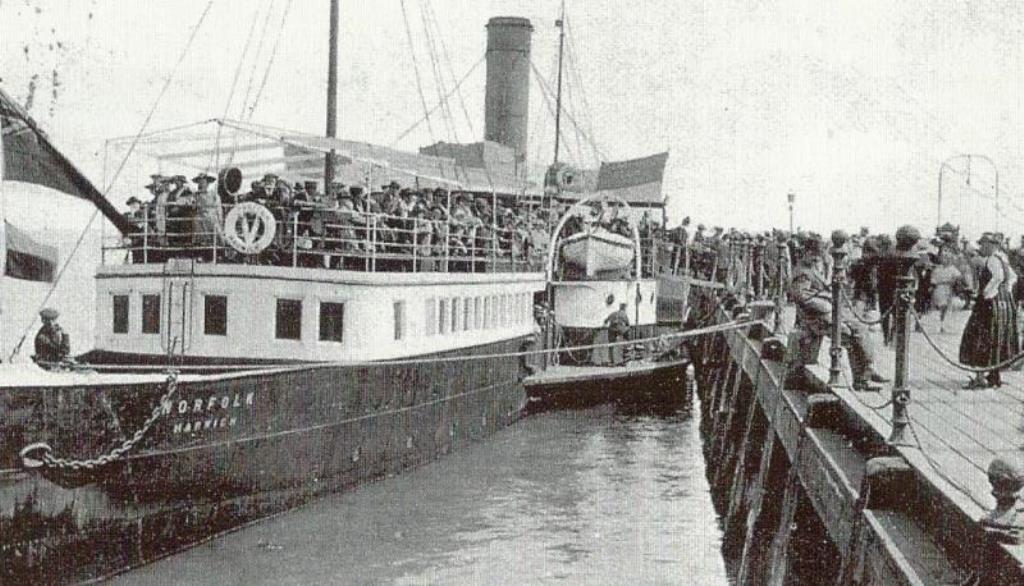

On the Quay a few early folk make their way down to the pier to board the Harwich steam boat. Some are seafaring men in thick blue jackets, and loose blue trousers, who saunter along with their hands in their pockets, perfectly indifferent to the mist, or the cold biting wind from the northeast. Some are engaged in building ships, and are off to Harwich on business. Others trade in old wine bottles, and second-hand articles, and are off to Harwich to make large purchases from careful and thrifty house-wives; women in thick plaid woollen shawls, stout boots, and large market baskets, full of chickens and fresh butter. These have been carefully covered with white linen cloths to protect the produce from the inky mist off the river which would rob the butter of its brightness, and the chicken of their freshness.

Alongside the pier or landing-stage lies the Harwich steamboat, fastened to the shore by stout ropes to prevent her floating down the river and off to sea, anxious, no doubt to escape from the foul and grimy water in which she has been imprisoned during the night. The bell rings at half-past eight, a few dilatory passengers quicken their pace in order to be in time. The captain takes his station on the paddle-wheels and gives the order “let go”. The paddle-wheels revolve the timbers of the vessel creak and strain, the black smoke rushes from the funnel, and the steamer is off on her short voyage.

The captain is a fine, strong, burly man, who has had his share of foul rough weather for many years, but his black glossy hair which escapes in youthful curls from beneath his sealskin cap, proves that neither adverse winds or tides, or the cares and responsibilities of a steamboat, have made him careworn or unhappy.

The man at the wheel has wrapped his hands up in warm mittens as a protection from the cold wind. One of the crew is stationed at the bow to look out for barges, buoys, and boats, whilst another who evidently suffers with tender feet, sells Barcelona nuts [a type of hazelnut] to the passengers to cheer their spirits and prevent sea-sickness.

Half-a-dozen passengers walk up and down the deck, stamping their feet and blowing the ends of their fingers. All the rest are down below where there is a good fire and comfortable shelter from the weather. Two or three old ladies are sitting on camp stools round the stove, drying their shawls, and enjoying an uninterrupted chat.

At the further end of the cabin is a poor woman thinly clad, with an infant in her arms, whose husband has met with an accident whilst dredging for stone. Wrapped up in her cares and troubles, she keeps away from the market ladies. The rest of the passengers sit on the seats arranged on each side of the cabin, chatting and smoking, strolling occasionally to the little bar, where the stewardess sells glasses of spirits which appear most acceptable to those gentlemen who have previously indulged in the luxury of Barcelona nuts.

And so a pleasant hour is spent, even on a misty January morning and on landing at Harwich all take different ways, bent on different pursuits, whilst fresh passengers go on board, and so a never-ending tide of men and women keep flowing on between the towns of Ipswich and Harwich”

© Renee Waite

Highlight Magazine 197. (Autumn 2019.)